The Maoist Experiment Lives on

Is revolution dead, confined to the annals of history? Just when you thought that die-hard Communist states like Cuba and North Korea are isolated relics to a past which is already beginning to seem distant, and that the future holds no prospect for the kind of liberal humanitarian ideals that blossomed in the 1960’s and 1970’s, a place like Marinaleda pops up out of nowhere. Located among the gentle undulations of the endless olive groves of southern Spain, this little village is a unique example of a Maoist commune that has not only survived, but continues to flourish.

Up until twenty years ago, Marinaleda was a typical sleepy Andalusian village, where nothing much happened and the poverty-stricken population carved a meagre existence out of seasonal work, picking olives on the vast estates of the landed gentry much as their folk had done for generation upon generation. It all changed when Sánchez Gordillo, a former schoolteacher, was elected mayor in 1980. As founder of the SOC (Sindicato de Obreros del Campo) this young radical intellectual had gained a reputation as a champion for the rights of the jornaleros, the land labourers who had neither land nor fixed employment, and when he succeeded in mobilising the support of the local socialists, Maoists and anarchists, Sánchez became a powerful voice for reform in this forgotten corner of Andalucía.

Once elected, the first thing he did was to rename the streets, swapping the names of Spain’s (in)famous generals to those of popular cultural figures like Federico García Lorca, Miguel Hernández and Pablo Neruda, as well as international revolutionary icons such as Salvador Allende and Ernesto “Che” Guevara. But there was more. Turning into “Avenida de la Libertad”, the unsuspecting visitor will encounter the unusual sight of a policeman who has not carried a gun or issued a parking ticket in almost twenty years, but delivers the post and runs errands instead. Though he still does so in uniform, his car is now simply marked “Ayuntamiento” (town hall); this transformation of the local police force from a source of authority to a municipal department like any other was an important victory for the anarchists and pacifists in Sánchez’s following.

After twenty years of uninterrupted service in office, the mayor is keen to point out that his movement has matured into a respectable political organisation, which he describes as: “…independent, populist, anti-capitalist and pacific”. Though Sánchez Gordillo shirks the word “party”, with all its power-game and behind-the-scenes connotations, it has been the vehicle through which he has been able to achieve so much in the past two decades, transforming Marinaleda from a feudal village into a progressive community. Back in 1980 few could have imagined that he would make any mark at all, much less remain in office for so long—during the last elections Spain’s only “Maoist” mayor won over 80 per cent of the vote.

It is a powerful endorsement, but this popularity is a direct result of the successful policies that Gordillo has put into effect, starting with the persistent campaign for land reform that he carried out in the 1970s, as leader of the SOC. “It was hard, our demonstrations and mock-occupations of the land were met with violence, but we endured, and in 1982 the Junta de Andalucía purchased 1200 hectares for the villagers to work themselves”. It was the first time this had happened in Andalucía, a region where two per cent of the population still own 50 per cent of the land and old aristocratic families such as the Duques de Infantado and Alva still own over 50,000 hectares around Marinaleda alone.

The land reform empowered the labourers, helping them to provide for themselves, but this required organisation and co-operation, so an agricultural co-op was established in which everybody has an equal share—everybody who contributes towards it, that is. The local slogan “The land belongs to those who work it” is telling of the attitude that prevails here. The system of communal work and co-operation that was subsequently developed is both a central feature of the town’s collective system and a vital ingredient in its success and survival. The co-op operates 352 hectares of olive groves whose consistently high yields attest to their careful nurturing. Intent on controlling the entire process, from harvesting through to processing, packaging and merchandising, the villagers set up facilities such as a processing plant and an olive mill in structures which not so long ago still represented the power of feudal lords. Building upon the success of its range of olive products, the co-op’s own brand name, Humar, now also carries products such as artichokes, peppers and beans.

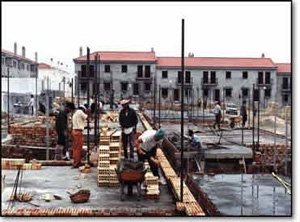

Marxist theories on the nature of work, according to which “generic man” should perform a range of different duties, influenced the unusual decision to rotate the more menial tasks, but it soon became apparent that more specialised, skilled jobs like management required full-time professionals. Such concessions to their utopian egalitarian society notwithstanding, the people of Marinaleda are proud of their achievements, and rightly so. Their growing agricultural concern has significantly raised the standard of living, though the villagers would be the first to admit that maintaining a truly democratic and communal system is hard work. An example of this are the over 100 annual assemblies at which all major decisions are made by majority rule. Another is the Domingo Rojo (red Sunday), during which people give up free time to work on public projects. This innovative project of Sánchez Gordillo has led to the completion of facilities hitherto unheard of in Marinaleda: a civic centre, new town hall, parks, a sports complex, day-care centre, theatre, secondary school and even a local TV station. The more than 200 homes that have been handed over to local families by means of a lottery system remain the most impressive achievement, as well as the enduring legacy of Gordillo’s communal experiment. The villagers who work together to construct these homes do not know who will occupy them until the day of the lottery, yet they work hard, knowing that if it isn’t their turn this time, it will be soon.

In a world in which materialism and cynicism reign supreme and the less fortunate wallow in self-pity, it is good to see people working together to improve their lot and form the kind of community of which we are all envious. The presence of a collective commune in the plains of Andalucía is both an odd and heart-warming phenomenon at the same time, and though it is based upon principles that have gone out of fashion long ago, the fundamental human issues addressed in this fascinating social experiment have continued relevance for us all.