Organic architecture – mankind and nature in harmony

We see it all around us; urban jungles of concrete, glass and steel that look impressive on the drawing board, imposing when first delivered shiny and new, but ultimately sad and neglected as they form part of a growing collage of rusting, rotting structures that require constant maintenance and investment or else they add to the desolate landscape we’re creating. Detroit, Mexico City, Sâo Paulo and Moscow, the examples are many, but you needn’t look too far to spot the concrete rot and urban decay, for it surrounds us in many cities and exists even in the most picturesque.

From Monaco to Manchester, ill-advised designs or the actual lack of design, planning and consideration seem to be the norm, rather than the bashful exception, and the individual actions of many different developers add up to the often austere, artificial and not particularly human-friendly environment we have created for ourselves. We leave nature behind to live in urban centres, but with the exception of some parks, most cities are jungles of unfriendly, unyielding materials whose ultimate decline ushers in a host of social problems.

This is partly due to a scale that dwarfs the very societies they were intended to serve and the use of harsh materials, the lack of softening green spaces, and in in general terms the unforgiving density of buildings, roads and traffic that makes many urban centres and high-rise suburbs around the world a bit of a hell. It is out of a reaction against this that the flight to the new suburbs of the early 20th century first took place, but these too have now become so big and sometimes monotonous that the original purpose is lost. In an age where sustainability is becoming a gradual need, we look to organic architecture for inspiration.

A battle of philosophies

Architecture is often regarded as the science of design, but whereas the shapes given to the edifices created is central to this discipline, there are many other facets that are almost as important, especially when you regard it not just as the abstract exercise of construction in its own right, but believe that architecture has a vital social role to play in shaping our urban landscapes. If it cannot be denied that buildings, homes and urban planning in general affect individuals and societies, then it follows that a gentler, more beautiful, spacious and nature-friendly urban setting is also conducive to a happier, healthier society.

Architects have been pondering these issues for centuries, and increasingly so since the right to prosperity and happiness became a thing a little over a century ago, and it is out of this that movements such as organic architecture evolved. It was just as mankind’s technological and industrial advances enabled it to bend nature to its will and create new artificial materials and densely-packed, mass-produced housing, that the first reactions against this form of soulless, automated living took root. Already at the turn of the 20th century, Art Nouveau sought inspiration in the complex, organic shapes of nature for the design of buildings, furniture, art and jewellery.

The rationalist, functionalist thinkers who would dominate much of the 20th century and so far most of the 21st, saw the world through different glasses, abhorring the apparently chaotic variety of organic styles and preferring instead the imposition of rigidly simplified linear lines – minimalism. Unlike William Morris and other members of the Arts and Crafts Movement, they eschewed the use of more natural materials such as wood, stone, ceramics and cork in favour of steel, polished stone, chrome, glass and concrete, their favourite material. From Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius to the Brutalist designers of Fascist Italy and Soviet Germany, austere functionalism was the dictate.

Shapes, materials and layouts inspired by nature

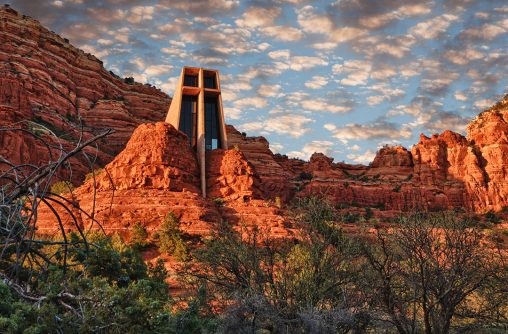

If much of the 20th century – and our present urban world – was shaped by the latter, there have still been notable movements that have fought it or sought to assimilate the rational and technological thinking of ‘modern’ architecture into a human and nature-friendly philosophy. Organic architecture is perhaps the most important of all of these, and its desire to find a harmony between people, their habitat and the natural world dates back to the early 20th century but is all the more relevant today, not just in terms of the need to protect the environment, but also to keep our ever-expanding urban centres liveable.

Early exponents include some of the greatest names in architecture, such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Alvar Aalto, who are not exactly known as tree-hut building hippies. Both employed the latest technologies and building techniques, were fully engaged with the modern world and designed important structures for it, but they also viewed the site, the plot of land as a sacred and finite gift that the architect, and mankind in general, has to treat with respect. Careful consideration should therefore go into the design process, and this produced long planes in the case of the Lloyd-Wright’s Prairie Houses, and a love of wood in the modern designs of Aalto.

Antoni Gaudi came from another direction, espousing the traditional crafts also seen in the Arts and Crafts movement and the weirdly organic shapes of Art Nouveau. Like the Austrian architect Hundertwasser, he took them out of the ‘real world’ and into a realm of otherworldly fairy tales, and both Barcelona and Vienna are so much the richer for it. More than them, the other organic architects have their roots in the modern design movement, but instead of interpreting it in an industrial way, they sought to include, not shut out or delete nature. This philosophy defines organic architecture in everything from flowing, natural forms and styles to the use of wood, natural stone, intricate brick and plasterwork, and even recycled tiles and ceramics.

An approach for the 21st century?

Architects such as Rudolf Steiner didn’t walk away from modern austerity, but when he did use concrete there was a complexity in his designs that softened harsh edges and replicated the complexity of nature. Rounded shapes are much loved by organic architects but not a requirement, as shown by Frank Lloyd Wright, who coined the phrase when explaining the need for architecture to work not only in rational and technical terms, but that it should also consider the psychological and emotional wellbeing not just of the individuals that use buildings, but also the broader society that interacts with them every day.

Looked at in this way, architecture should be rich in diversity of materials, styles, shapes and inspiration, but while it can stand out in its own right organic architecture seeks not to diminish nature but to complement it as much as possible, and harness natural beauty for the wellbeing of the human occupants. This affects volumes, functionality, internal distribution, views and the use of materials, including recycled ones, but above all it depends upon a benevolent and idealistic urban planning ideology that wishes society to be the very best it can – happy, healthy and inspired by the beauty of nature. Maybe organic architecture is the answer to our present and future needs!

First published in Essential Magazine